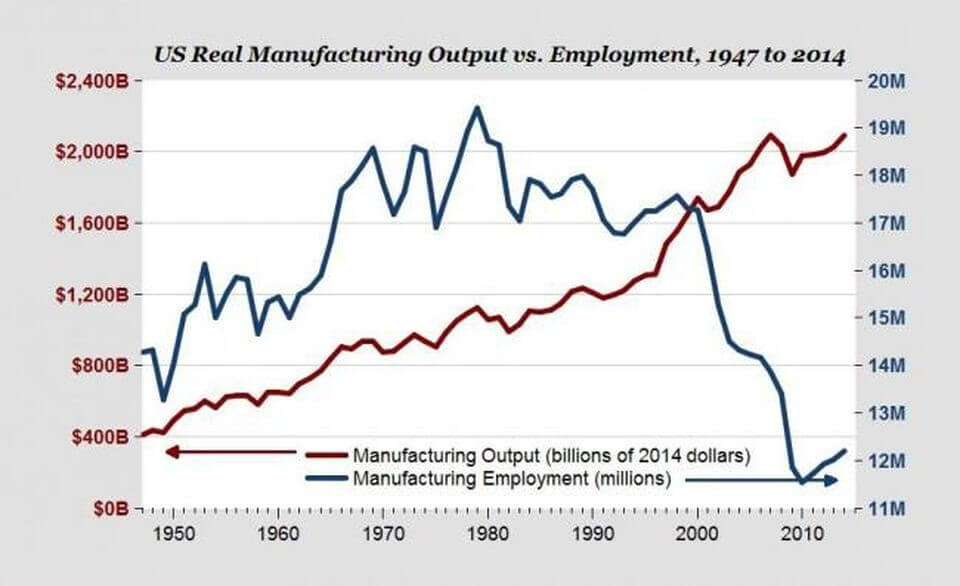

U.S. manufacturing output increases even as U.S. manufacturing employment declines, suggesting a central role for automation in the post-Cold War decline in U.S. industrial employment.

Source: Forbes.com

My writing in general seeks to illuminate how the progressive side of our debates thinks about major political issues. One thing that might be helpful, though, is to talk more about the things on which I agree with Donald Trump.

Finding things that fit into this category was difficult, of course—I am a staunch progressive. But there have been some things about which President Trump is right. One example came up during his campaign, when detractors were assailing him for his multiple bankruptcies. I actually see the ability of an entrepreneur to go through bankruptcy, survive, and reinvent himself or herself, to be a huge strength of American economic culture.

In many other countries, including those in Europe, bankruptcy hobbles failed businesspeople for many years, precluding them from trying again. But in the U.S., people can dust themselves off and try again in short order. The Ford Motor Company was actually Henry Ford’s fourth company, after failing in various ways on the first three. Had Ford been blacklisted due to the dissolution of the Detroit Automobile Company two years prior, the history of the automotive industry might look very different.

My thoughts on Trump’s version of his story are complicated. Clearly in the course of doing business, he has left many other people holding the bag when his companies go under. But he has correctly identified a strong driver of American innovation, and is certainly right to take advantage of our bankruptcy laws to try and create new ventures that keep this country at the forefront of many industries.

Another thing that candidate Trump got mostly right was his focus on China. That country has, for the past several years, been our largest trading partner, and there’s a lot to be said for the power of economic ties in contributing to the stability of the globe. But China’s trade policies have become increasingly problematic, especially as its global clout has grown. We’ve been long overdue for an American president to challenge the People’s Republic over its anti-competitive and unfair tactics.

First, let me put aside the issue of currency manipulation, which isn’t much of an issue at all. The global currency market is far stronger than the will of a single government—particularly one that doesn’t control the world’s primary reserve currency, the U.S. dollar. China’s goods have risen in price, and there’s not much its government can actually do about that.

Much more seriously, there’s plenty of nefarious things that China has been doing to increase its primacy within several of the world’s most important industries. The recent news about Huawei’s control over the 5G cellular data network is alarming, and it’s clear that China is not only protecting these companies to enable them to dominate many emerging tech markets, but also exporting its surveillance state.

For many years, China seemed to be on a path of trade liberalization, which helped it to grow into a global supply juggernaut by gaining the trust of partners like us. This served to cool geopolitical tensions, at the same time that it brought hundreds of millions of its people out of extreme poverty, signaling a win-win for the world at large.

But as this was happening, the economic situation in the U.S. grew more complicated, with various factors contributing to the decline of the previously steady industrial job, and stagnating wages, particularly for those who hadn’t advanced beyond a high school degree. Even those of us with advanced degrees have been impacted; despite holding an M.B.A from an elite university, I was laid off from a firm in the auto industry in 2017, and jobs within an industry that viewed the future with uncertainty were harder to come by than before.

While I’ve since begun working for Braver Angels full time, some experiences in my job search were instructive. Some of the most aggressive hirers in the automotive industry are now Chinese companies. In fact, that country made a big commitment to electrifying the industry, and China is now by far the largest producer of electric vehicles in the world.

One of the ways they’ve done this is through partnerships with foreign companies. While this policy has recently been eased, for many years it was not possible to do business in China without a partnership with a Chinese company. Because of the country’s lax intellectual property laws, this essentially meant that any company who wanted to sell their wares in China had to essentially transfer a bunch of its patented technological secrets to Chinese companies.

There’s been a major debate in the U.S. about how much of our stagnating employment should be blamed on jobs leaving our shores for lower cost countries like China. Indeed this has certainly had an impact, but according the government, that only accounts for a quarter of the decline. This isn’t insignificant, but it points to the fact that the labor market is a much more complex and interconnected one than previous generations faced.

Much of this decline is due to automation, with jobs shifting from low-skill to high-skill focuses, like being able to run the more complex machines that make our goods. In a purely economic sense, this is a good thing, since it opens up opportunities for Americans to “move up the value chain,” so to speak. Rather than just making these goods, we need more people to design and engineer them, and to understand the market so these products can better connect with consumers. Naturally software is an integral part of this whole equation, so if you’re worried about your employability, coding is a pretty sure bet. It’s even a good idea for those without much education; some software firms will hire someone without a high school diploma if they’ve done well in a coding boot camp.

While he’s often shorter on specifics, President Trump has pointed out China’s unfair trade policies, most of which were already in place before our current trade war kicked off. But the trade war has certainly done nothing to make the situation better. To be fair, it did at one point seem like the American president was on the verge of outmaneuvering the Chinese president by putting a huge amount of pressure on the latter’s economy. But he’s done so on the backs of American workers, particularly farmers, who are suffering hugely due to the tariffs.

And Trump has been fairly inartful with his negotiations, which has helped to pin both himself and President Xi into corners from which they’ll find it difficult to emerge. On top of this, there’s scant evidence that President Trump understands that Americans are the ones paying the import tariffs, and he’s been bragging about how much money the government is making off of them. (This is 100% real. His own staff says he doesn’t understand this.)

And it’s not just that the American-based importers actually hand over the cash. Tariffs raise prices across the board in an industry, hitting consumers wherever they shop.

Indeed, this happens to be a temporary boon for the American manufacturers, but it’s deceptive. When American goods get more expensive, it has a general impact on the market as a whole, and with prices rising, quantity sold goes down, worsening economies of scale.

Trade barriers simply prevent the efficient allocation of goods and services. It’s not that much more complex than that. My friend Justin Naylor wrote about this issue recently, but aside from overstating the supposed salutary effects of tariffs, I think he misinterprets the idea of comparative advantage.

“There’s a passage in Adam Smith’s classic text of early capitalism, ‘The Wealth of Nations,’ in which he discusses the rationale behind free trade between countries. He compares the family of nations to an actual family: ‘It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family never to attempt to make at home what it will cost him more to make than to buy.’ … But what would Smith say if in his example the metaphorical family could not produce anything better or more cheaply than other families? What if there were no meaningful work left for the family to do…?”

The fact is, every economic actor has a comparative advantage. It may not be a direct advantage over another country in terms of cost, but one country will always want to do something different from another because of differences in their opportunity costs of doing something else.

China could probably grow all the soybeans it needs, and probably even more cheaply, but it would rather use its land and labor to grow rice, buying the soybeans from us. But it’s no longer doing as much of that, because of the retaliatory tariffs it placed on our soybean crop. Which means that in the rush to save our steel industry, which no longer has as much of a comparative advantage versus China, we’ve shot our farmers in the foot, all while raising car prices around the world so the electric cars we need are further out of reach.

I very much agree with President Trump that China, with its unfair trade tactics and its backsliding into economic illiberalism, is a problem that must be addressed. It’s about time the WTO stepped up and declined to be cowed by the country’s economic might. But tariffs, so agrees nearly every economist in the country, are not the way to do it.