Michael Harrington

Editor’s Note: This piece is an edited version of two essays published at Braver Angels’s website in August and November of 2018. We re-publish the two pieces, in conjoined form, due to their exceptional observation of the trends of polarization in America, an important focus of Braver Angels’s journalistic and scholarly efforts.

How We Are Divided

American politics has grown increasingly polarized over the past 20 years, degenerating after the 2016 election and in the Trump Presidency into all-out partisan warfare. Observing from the sidelines, a significant portion of the voting public has begun to sense a real danger in this fracturing of partisan politics, and are searching for solutions.

With many competing media narratives, it’s difficult to make sense of it all. Our first instinct is to ask why we are so polarized, while some investigators cite data to question even if we are so divided on our differences. But putting our recent experience into historical context can illuminate how we are actually divided and have been for most of our nation’s history. Since divisions are not necessarily polarizing, we can then examine what specific factors are driving us apart. [The first installment of this series will focus on how we are divided while second will address this related question of why we are polarized.]

A number of periods in our history were marked by sharp partisan divisions. We can cite Jefferson’s yeoman farmers against Hamilton’s strong federalism, and Jacksonian democracy vs. New England financial interests supporting the Second Bank of the U.S. Obviously we had the Civil War split between the industrial North and slave-holding South. At the end of the 19th century we again had a split between mid-Western agricultural interests and the financial centers in the East over what William Jennings Bryan coined as the Cross of Gold.

A CENTURY WHERE NOT MUCH HAS CHANGED

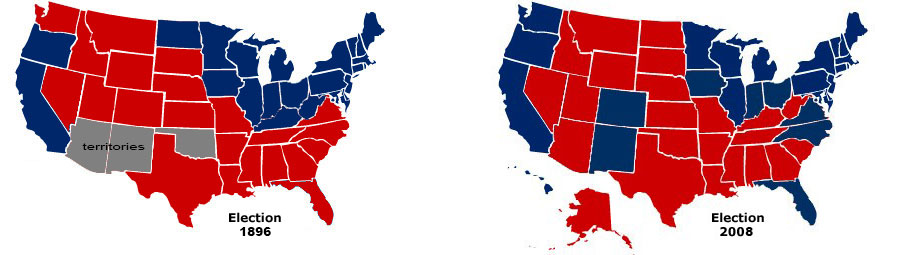

We see from this comparison of Electoral College results that the inhabitants of regional areas vote consistently along partisan lines, albeit for different reasons associated with their geography. In 1896 the colors are flipped as red denotes Democratic states and blue denotes Republican (gray areas were not yet states) – but the split is almost the same, showing how the parties flipped while the voters maintained similar political preferences.

The first thing to notice is that most of these conflicts were regional and associated with certain economic industries, typically agricultural interests pitted against industrial and financial interests. These divisions were driven quite naturally by competing material interests defined by their rural vs. urban geography and, with the exception of the Civil War, were managed and resolved through the democratic electoral process.

Fast-forward to the end of the 20th century and we find that our partisan politics are still largely divided by rural and suburban vs. urban splits. Divisions based on economic sectoral interests persist in our regional economies, but with a more homogenized national economy, they are not as salient. The political calculus today seems driven by something more, and this is the puzzle we are trying to understand. In the contemporary case, once we look at the voting data, state county maps may offer a more accurate representation of the true geographic pattern than state or regional comparisons.

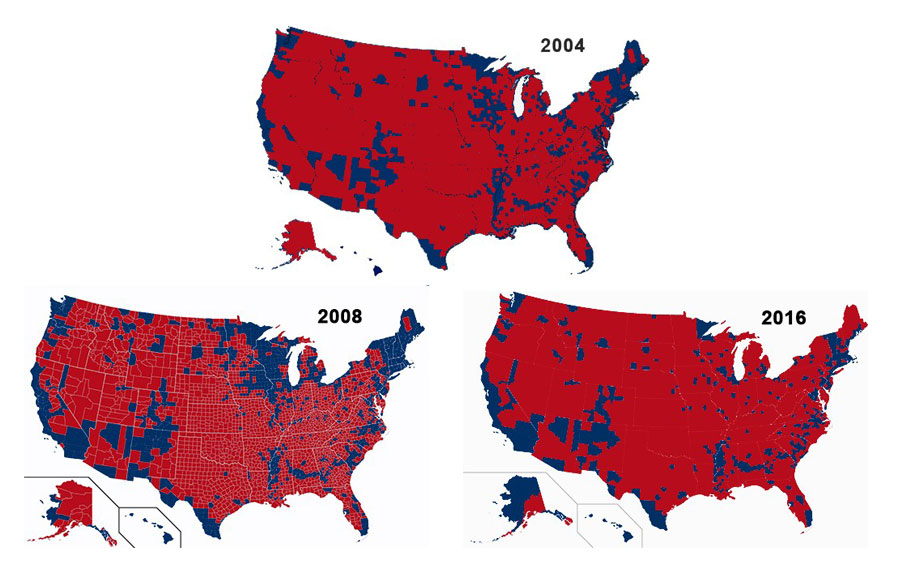

COUNTY PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION VOTING TRENDS BEFORE, DURING, AND AFTER THE OBAMA PRESIDENCY

Without getting into Electoral College math, we can see that the big shift in recent years was in the Great Lakes region, where Barack Obama won every state in 2008 and Hillary Clinton lost every state in 2016 except for NY, IL, and MN. We can attribute this to the fate of the Rust Belt economy over the intervening years. (We’ll also leave the contentious debate between the primacy of geography or of population for another day’s discussion, when we discuss the logic and effect of the Electoral College.) Suffice to say that electoral geography offers valuable insights into our voting results.

It would be impossible to capture this pattern in our analysis without employing some kind of geographic explanatory variable. This is where exit polling may fail us. Exit polling is sampling data from survey questions asked of voters after they exit the voting booths. The surveys inquire into numerous classifications of voters, but rely mostly on demographic characteristics such as race, gender, ethnicity, age, income, etc. We can see that exit poll question give us exit poll answers – there is no effective way to capture the urban, rural, suburban divide except by comparing different exit polls. Furthermore, exit polling introduces sampling bias – for instance, pollsters have discovered that liberals are more willing to reveal their votes than more traditional conservatives. Pollsters try to account for this bias.

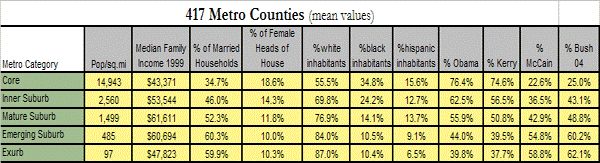

But county-level data offer a different approach. All votes are reported by county, and counties offer numerous demographic data based on the prior census. More importantly, counties offer a rich population set of more than 3,140 data points without any need for sampling. This allows us to regress the demographic data against the vote shares to determine with a high degree of confidence how county demographics affect voting preferences. In other words, what demographic characteristics: age, income, race, ethnicity, household formation, gender, etc. explain how the county residents vote? Counties also offer such data as median family income, and population density.

The results are revealing. Using regression analysis to run votes shares against the prior census shows that the most significant predictors of how a county’s residents vote are population density and household formation that varies between married and female heads of household. Race, ethnicity, age, gender, children, income, are all insignificant by comparison. In statistical terms these two variables explain roughly two-thirds of the variation in voting patterns. This may seem counter-intuitive but two anomalies help affirm the results.

First, black vs. white, or white vs. non-white, as a race variable is significant until female heads of household are introduced into the equation, then the black variable gets subsumed by female heads of household. According to data from the 2000 census, the correlation between the black population and the female heads of household population is an astounding .8, where 1 is perfect correlation. This suggests that black female heads of household are voting more in concert with female heads of households of other races than they are with married black households.

The second anomaly is the robustness of the population density variable, which is perfectly monotonic across metro county classifications and voting preferences. What this means is that across the entire nation, as population densities increase from rural counties to exurbs to mature suburbs to inner suburbs to core metros, the vote goes from solid Republican to purple swing counties to solid Democrat, without deviation.

This is quite remarkable and begs for an explanation. It’s important because the answers will help us understand why people really split along stark partisan voting patterns – is it primarily because they are white, black, Hispanic, female or male, young or old? Or is it because of lifestyle choices they have made that correlate more closely with one party identity than the other?

There is likely no singular explanation, but one of the more persuasive is the divergence in material and policy interests among communities that vary in accordance with their population density. Urban singles, with or without children, have different policy priorities than suburban and rural married couples. These differences are somewhat reflected in the policy platforms of the two parties. For instance, cheap public transportation and rent control vs. low property taxes, good roads and low gas taxes; more social welfare programs vs. lower income taxes and more autonomy; better public schools vs. more school choice.

Of course, this cannot be the whole story. As Jonathan Haidt outlines in his studies on political ideology, there is likely a strong component ascribed to different orderings of moral values and sensibilities. Blue voters prioritize liberty, care, and fairness, while red voters have a more comprehensive set of value priorities that includes loyalty, authority and sanctity. This naturally leads blue voters to support subnational, multicultural identity groups that are historically disadvantaged in our society, while red voters tend to privilege an “American melting pot” with a distinct national identity and culture.

These value orderings tend to correlate with urban, suburban, and rural lifestyle choices. With the constant influx of new immigrant groups and young people, social change occurs more rapidly in urban communities. Exposure tends to inure us to change and make us more adaptive, whereas culturally traditional rural and outer suburb communities are less exposed to rapid change and thus can be more resistant.

Another way to approach this is by looking at the voting data on religion. The American populace can be described as religious, but the nature of belief that implies varies widely. Orthodox denominations and social conservatives attend church regularly and tend to vote red, while heterodox denominations and progressive secularists lean blue. This explains why churches became Republican messaging centers under campaign strategists Lee Atwater and Karl Rove.

However, we can put too hard an edge on this when judging the “other” and I hesitate to use the labels of liberal and conservative because of their ideological baggage in our political discourse. What journalists have revealed in their narratives of America by crisscrossing the land and interviewing residents, is that we have more in common than not. I would classify most of America as tolerant and traditional, rather than partisan, ideological, or political. This means average Americans have one foot in the blue camp and the other in the red camp.

The important thing to note is that policy preferences that are divisible, like most of those above, allow for the compromise and convergence necessary to a functioning democratic process. If we are rooted in political camps that have solidified into our immutable personal identities, no such compromise is possible and our democratic governance becomes unworkable. We should probably focus more on what people do and where they live rather than who they are.

We have not yet answered why our plain and obvious differences have caused us to become so polarized into opposing camps when it comes to party preferences. We’ll save that discussion for another day. But our American political experiment has enabled us to self-govern a large, diverse, pluralistic population across a very large landmass for most of our history. There’s no inherent reason why we cannot do so today.

Why We Are Polarized

We have examined how Americans have been divided politically today and for most of our nation’s history. But political divisions do not necessarily become polarized into stark and uncompromising positions represented by two-party combat: A divided nation is not the same as 50-50 polarized nation. In other words, divisions are necessary, but insufficient, to explain our level of partisan polarization. The question we face today is: What polarizes us beyond our mere divisions?

Much research and polling has been conducted to answer how and why we are polarized. Scholars have measured the ideological consistency and divergence between the two parties in Congress, showing that that legislative body is more divided now than at any time since the end of Reconstruction. Others have focused on partisan media bias, both mainstream and alternative, and how those biased networks create information bubbles among their viewers. Still others have examined psychological factors that have sorted the electorate into opposing ideological camps. Ironically, it’s been said that the most conflicted day in American society today is Thanksgiving.

One can point to many interrelated factors, but most of these trends can probably be traced to various changes in political and social culture over the past half century. These changes have been enabled along the way by technological advances affecting political news media, election campaigning, and social interaction. Finally, the citizenry has begun to sort itself spatially—urban vs. suburban/rural—in response to these various pressures. This spatial sorting circles back to amplify our historical legacy of geographic divisions based on economic interests. Perhaps the best way to make sense of all this is with a historical narrative rather than a compendium of statistics.

The 1960s was a seminal decade marked by the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War. These events brought various conflicts to the surface – generational, racial, ethnic, gender and sexual orientation, ideological – that came to be reflected in the two political parties as those parties began to target these various constituencies with electoral appeals. After their chaotic 1968 National Convention in Chicago, the Democratic Party changed its delegate rules for party nominations to greater reflect changing demographics. This fractured the party into many different camps. Soon after, the Watergate episode and Nixon impeachment split the Republican party between the establishment Rockefeller wing and a new conservative wing heralded by Ronald Reagan.

The fracturing in party cohesiveness was reinforced by various rules changes that served to weaken hierarchical control within the party apparatus and empower individual candidates in election campaigns and policymaking. Candidates became more like political entrepreneurs rather than good partisan soldiers and found success by appealing to targeted identity groups rather than more consistent party principles. This came to the fore of national politics with the 1972 Nixon-McGovern election and was reinforced by the Carter-Reagan face-off in 1980. Political freelancing would soon become the norm, but could also still coalesce around strong party leadership, as it did with the Gingrich and Pelosi majorities in Congress.

During the 1970s and 80s, traditional print and broadcast media was under pressure from new competition in cable television and Talk Radio that threatened their hold on market share. The logical marketing strategy to hold onto audience shares was to give readers and audiences what they wanted, especially on hot-button emotional issues. This strategy fed the rise of infotainment, celebrity scandal, and political opinionating. These emotional triggers soon dominated our air waves.

Not surprisingly, most major media companies found their audiences in the urban and suburban communities and tended to interpret politics through the lenses of those communities. It was also not coincidental that most of the reporters and journalists who staffed these companies also lived and worked in these communities. Many journalists, some still operating in 2018, came of age during the Nixon impeachment. In that experience, they saw corruption tainting a Republican Party that happened to be aligning, over time, with non-urban voters and the agrarian South associated with traditionalist social and cultural attitudes. All these factors have contributed to and accentuated the urban media bubble, which shifted away from Middle-American concerns and attitudes over time. The divide became much more contentious when Rupert Murdoch’s FOX News channel stepped into the void abandoned by the old media, and filled it with content meant to appeal to non-urban, non-Democratic viewers.

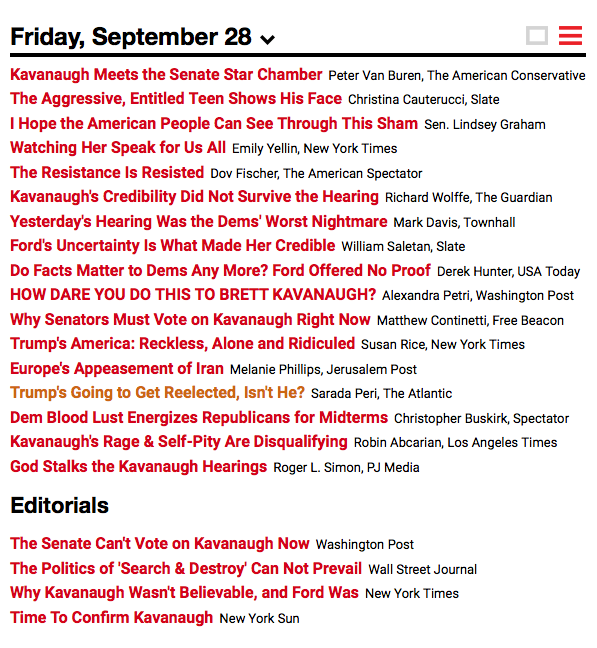

This screen capture from the news aggregator RealClearPolitics shows how our media organizations, their reporters, and their audiences now reside in different universes with opposing views of reality.

The final disruption of traditional broadcast and print news media came with the dawn of the Internet. As digital technology has disrupted most of the ad revenue streams of traditional media, the industry is less able to cope with adaptation. With the proliferation of news blogs and social networks, citizens are disconnected as they self-select their news sources. The main focus for media relevance is now an amalgam of celebrity politics and, in order to maximize audience share, one must choose sides and perfect the art of click-bait, sound bites, and photo-ops. The more outrageous and controversial the scandal, the better. It’s a matter of survival – one cannot report the news if one cannot stay in business.

This ideological polarization that has infected the two parties and media is partly a reflection of, and partly a catalyst for, the polarization of the electorate. An important transformation in American social culture over the past century has been the rise of new or formerly disenfranchised groups that seek greater democratic representation and political influence. These groups have naturally sorted themselves into identity groups based on race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and social class. As a result, traditional class divisions based on socio-economics have been largely subsumed by biological identity. While one can list many positive effects of identity coalitions in terms of opening up democratic politics, the problem arises when it comes to democratic compromise. Identity politics makes it difficult to compromise policy positions when those positions are defined by immutable identities.

These battle lines have been drawn over many contentious issues that are likewise resistant to compromise, such as moral value differences dealing with faith, religious conscience, abortion, and differing conceptions of marriage. Political rancor has also bled into judicial appointments and rulings, professional sports, education, and entertainment and cultural expression. The result, as we have seen, is a series of win-or-die wars over every possible political, economic, or social skirmish. The battle is fought over who controls the message, the agenda, the news cycle, policies, electoral rules, campaign funding, and more. It seems that if everything becomes a matter of win-or-die, one had better get off the sidelines and join the winning team. What we get is smash-mouth politics, where ultimately power prevails.

How does one respond rationally to such extreme polarization, as we witness the dysfunction and disintegration of democratic politics and social organization? Does one engage or disengage? We’ve seen the rise of both trends as citizens become either more activist or more disengaged from party politics. In recent years, we’ve seen the rise of the Tea Party on the right and the Occupy/ #BlackLivesMatter/ #MeToo/ Democratic Socialist movements on the left. In the meantime, the fastest growing faction in American politics is now “Unaffiliated,” and likely “Disgusted.” This fracturing of the electorate has introduced a new volatility to electoral and policy outcomes. The successes of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders attest to these unconventional figures’ disruptive appeal to the angry and disengaged. This is no longer your father’s party politics.

So what can we do?

This brief history points to several driving explanatory factors: political parties, the media, and the cultural narrative. The political parties as currently organized have no incentive to reverse their divide-and-conquer electoral strategies, at least not until the electorate demands different politics. Certainly there are wings within each party seeking to upset the apple cart, but neither party can abandon identity politics without suffering the existential threat of persistent electoral defeat. The news media business model is hanging on the thin threads of political conflict, so we cannot expect these companies to fall on their swords either. That leaves it to us – the voters.

A time-proven antidote for the dysfunction of democratic politics is electoral competition, which forces accountability. Unfortunately, many of the solutions for changing institutional rules and practices actually reduce competition in favor of one party’s constituents or the other’s. The arguments for and against the Electoral College, the Senate, and winner-take-all elections rarely present a balanced or comprehensive analysis. Certainly gerrymandering of congressional districts is anti-competitive, but the uncompetitiveness of districts also reflects voters’ deliberate political sorting.

From a practical point of view, the individual citizen who seeks better functioning of our political democracy should advocate against unnecessarily politicizing non-political issues. Don’t politicize; de-politicize, if you can. It would also behoove us all not to meld our personal identity to our political preferences, but rather to promote political and moral principles that transcend our person. Lastly, a major psychological detriment has been how we signal our own virtue as we negatively characterize our political opposition and stifle dissent. I would gently suggest this is more a projection of our own character rather than the ‘other.’ Let us be principled, but humble and generous.

Our American political experiment has enabled us to self-govern a large, diverse, pluralistic population across a very large landmass for most of our history. It would be a shame to let it disintegrate for a self-congratulatory, but temporary, case of political victory.

Michael Harrington is a political scientist, policy analyst, and writer living in Los Angeles. He has extensively researched the red-blue divide in American party politics by focusing on county level census and voting data. He blogs at www.casinocap.wordpress.com and www.tukaglobal.com.