Rupa Ray has been to over 30 Phish concerts since 2016. It’s not unusual for “phans” to follow the jam band around from city to city on tour, particularly since the quartet draws from its deep catalogue to offer a completely unique experience at each show.

The atmosphere at the shows is freewheeling, with phans gathering in the parking lot ahead of time to share home-baked goods and sell home-made memorabilia, with clouds of weed smoke hovering over the scene. In the tradition of the Grateful Dead, it often feels like a big hippie party where everyone is free to let their freak flag fly, the crowd proud of the open and communal vibe they’ve created.

While the Phish community sees itself as inclusive and accepting, the demographic of the audience at the concerts is actually fairly homogenous. The band looks out from the stage at a sea of white faces—mostly men—with people of color much less numerous. As a woman of Indian descent, Rupa is a distinct minority.

Her experience at the shows is generally very positive, but every so often she catches a glimpse of a different undercurrent that runs beneath the outward openness.

“I’ve noticed people don’t interact with me,” she says. At times, when her group runs into familiar faces and they’re introduced, there’s a difference in the way she’s treated. “The people that we’re meeting will interact with everyone but me. They’ll say hi to everyone but me, they’ll act as though I’m not there, they won’t look at me, they won’t speak to me. It’s as though I were invisible, and I’ve noticed that specifically on a few occasions.”

Rupa is fairly light-skinned compared to other people of color, including those of South Asian heritage like her, and she acknowledged that her own experience is fairly mild in the scope of the larger phenomenon.

“I think that the more ‘other’ you look to the mainstream phans, the more it’s going to affect you in a sort of superficial way when you’re out and about.”

Like many communities that project strong identities into the world, the Phish phan world can be protective of its self-image. There can be a sort of reflexive defensiveness to the sort of criticism that might expose a rift in the façade of progressiveness. Adam Lioz found this out first hand in 2017 when he wrote an essay, posted on Headcount.org, that attempted to shed some light on this aspect of the phan scene that isn’t often talked about.

It’s a community in which he was deeply ingrained, but he wrote about opening his eyes only recently to how the experience of the shows could differ for people of color. Adam had done his research, talking to several phans of color and their partners, hearing about experiences like being “constantly asked where the bathroom is (‘100x a night, no exaggeration’)” with the assumption they worked at the venue, and being baselessly accused of selling counterfeit tickets.

The subconscious assumption that non-white concert goers couldn’t possibly be “real phans” came through in myriad ways, most of which were subtle enough that the self-styled progressive white phans just weren’t sensitive to them, even when they happened right in front of their faces.

Adam invited the community to start a conversation, and posted an email address where readers could engage him and take it further. The direct response to this email address was mostly positive, and from it a new activist group was born, Phans for Racial Equity, or PHRE. I was extremely proud of Adam, my brother, for having articulated the issue so well, and for being able to draw together a group of like-minded individuals to actually do something about it.

But the conversation went beyond that. The article had gone viral on various social media platforms, and in several venues including a major thread on Reddit’s Phish sub, all sorts of vitriol was unleashed, with countless posters calling him and his article stupid, and more profane dismissals of his message, like, “F— off with this virtue signaling ‘diversity’ garbage.” There have been online commenters that have assailed his motives, claiming that he was profiting from the attention (he hasn’t), and claiming that his entire article was a gigantic lie (it isn’t).

Adam has been busy helping to build out the infrastructure of PHRE, creating leadership committees and hosting calls and discussions, and fielding renewed interest in the group’s mission especially in the wake of an incident involving violence against people of color at a show at The Gorge in Washington state. Even after more than a year, the invective hasn’t stopped. Adam recently shared an email that he got just last month which underlined for me how damaging some of these online attacks can be.

The missive started with “F— you c—,” and didn’t improve much from there, calling my brother “an ignorant sh– stirring, sh– bag,” and implying he’s “a racist a–hole who wants to spread their bullsh– identity politics everywhere.” What really gave me pause, though, was the email’s final lines: “I better never see you [outside a show] I’ll tell you that much I know who you are because like my grandfather said ‘fools names and fools faces always appear in public places…’.”

Much more than just a threat to his grammatical sensibilities, this was a direct threat to his safety. And it came from someone who, in the same message, talked about his own experiences bringing people of color to Phish shows.

To be clear, this message is not typical of reactions to the piece. And Adam has taken even this in stride, telling me that he doesn’t feel actually threatened, more just sad that this element exists within a community that he had viewed as so welcoming and open.

What this email shared in common with many of the other negative takes on his piece was that because he was describing an experience that didn’t align with those of some phans, and had the temerity to challenge their group’s preciously held identity, his views should be cast aside as a direct attack on the community, discredited at all costs.

The challenges that Rupa has encountered online have been more subtle. She frequents a Facebook group called PHISH TOUR 2014, and there have been posts there that have been insensitive to people outside of the band’s core straight white male demographic, she says.

“I suspect that the people who share my reaction to it just don’t say anything, because it’s so much easier not to,” she lamented. “All the trolls are out in force, and nobody backs you up!” There’s also a tendency to question the legitimacy of group members who don’t fall in line based on their recency within the online group or the number of shows they’ve attended. It fits the pattern of ad hominem attacks by those forum members who perceive a threat to their group identity by those they see as insufficiently loyal or alien in some way.

At most Better Angels red/blue workshops, the red group brings up the stereotype that blues hold of them as racists. And often in discussing the “kernel of truth” the reds will cite the fact that we all hold certain biases within us, and for nearly everyone that includes racial prejudices. While this has never really struck me as a fully productive embrace of the spirit of the exercise, since it casts more of the blame on “society as a whole,” it’s an entirely accurate assertion that does have a real bearing on where we are as a country.

Even those who make it a priority to pursue racial justice are not immune to inherent biases. It’s clear that, while blues have focused more explicitly on combating the legacy of racism and the structures that perpetuate it, they are not necessarily paragons of equitable treatment towards those different from them. And when, as blues, liberals, progressives, Democrats, we deny this to save our own egos, we do a disservice to our own mission.

The blowback against phans trying to raise the racial equity issue is also instructive in showing us how the hatred that pours forth from the Internet is not confined to arguments between groups, but also within them.

“The instinct to be nasty to someone who’s in the same group as you and shares the same basic values, that’s something that I understand less,” Adam told me. “People see themselves as policing the boundaries of their group, and I guess in the case of my article there were a set of people who perceived the article to be an attack on their version reality.”

Kate Pazoles, who leads communications at PHRE, sees the issue in a wider context.

“To me, the timeliness of Adam’s piece was in looking at the Phish scene as a microcosm of the majority white spaces in the ‘progressive, elite bubbles’ that were completely shocked and confused by Trump’s victory in 2016.” She points out that while those scenes that were progressive, but which lacked substantial diversity, were caught off guard by these hidden currents, people of color were not.

Adam mentioned that there are plenty of affinity groups that have had their own pretty significant conflicts about which members are truly living the values of the group. Even PHRE itself has not been entirely immune, despite including exclusively members who agree with the message of the original piece. After a particularly heated thread on the group’s Facebook page, its administrators—including Adam, Rupa, and Kate—devised a code of conduct and flagging system that has served the discussions well.

“Ultimately a community creates norms for itself,” he says. “If the goal is to essentially build your notice and status within the community, and if communities start to adopt norms whereby being an a–hole does not provide you with that kind of notice and status then the incentive to be an a–hole goes down, so I guess that’s a big part of the solution.”

Within Better Angels there is also a push to have a positive impact on the online discourse, and I’ve been excited to work on a special Better Angels Code of Conduct with the help of Steve Saltwick, state coordinator for Central and South Texas. One of the unique aspects of our online initiative is a “social media pledge,” indicated by a frame around your profile photo, that indicates that you promise to bring your best self to conversations online.

Just like at our workshops, we want to ensure that people can be open and honest about their views, without fear of being demeaned or vilified. Because these conversations are important, both within our communities and between them, and we need to ensure that we can all feel safe participating.

Adam insists that the conversation on race in this country is still very much needed, as demonstrated by the fact that even some members of generally progressive communities exhibit some retrograde attitudes.

“The solution is to talk openly and address the issues openly, and when you do that you’re bound to run into some defensiveness. That’s fine, that’s part of the process, that’s to be expected, and if anything it’s evidence of the importance of the conversation.”

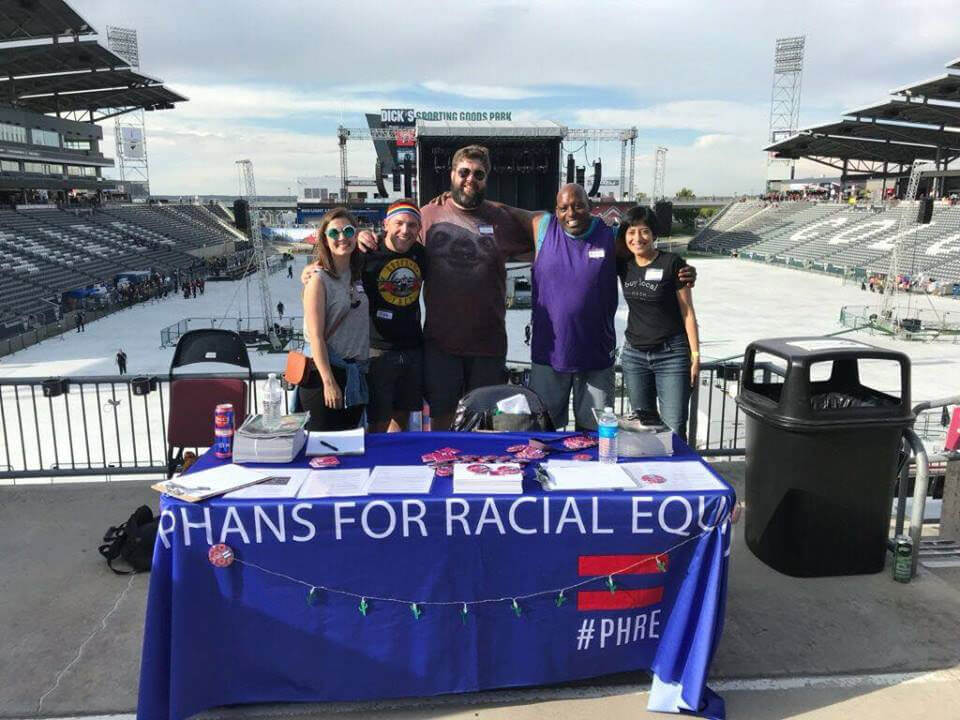

Photo: Members of Phans for Racial Equality (PHRE) working a table at a Phish concert at Dick’s Sporting Goods Park, Commerce City, Colorado. Left to right: Kate Pazoles, Adam Lioz, Mike Doris, Malcolm Howard, and Rupa Ray.

Randy Lioz is the Southern California State Coordinator for Better Angels, as well as a regular moderator of red-blue and skills workshops. He has spent his career in the auto industry as an analyst, consultant, writer and educator. Randy lives in Irvine, CA, and spends much of his time in front of a soccer goal or beside a friendly mutt. His column, The Lioz Letters, is published weekly at The Conversation.

2 thoughts on “Lashing Out in Defense”

TEMPERATE QUESTIONING OF DEFENSE

Yes, of course, to us, of sanity, the nasty responses to Adam’s article were out of line—the “road rage”—we hide behind on face book and twitter.

I would like to offer this though:

When it comes to intolerance, I liken the intolerance need to like a tube of toothpaste. As we become tolerant about so much that has been positive—tolerant of sexual differences, color—we have found a very sneaky, insidious way for our intolerance to manifest. Back in my day, we looked for every communist under a rock. If you had any association with a liberal arts college, if you supported Gus Hall, the leader of the American Communist Party to speak on campus, you were suspected of Communist leanings conscious or unconscious. You were not a N lover, or a Trump lover. You were a pinko. A communist pinko. and so was anyone with whom you had any inkling of association.

This is very sneaky for the reason: how can you become intolerant of intolerance. My sense it is like the toothpaste. You squeeze on it and the toothpaste has to come out some place. It is like, we have this need for intolerance often associated with anger, righteousness, being better than others; and, no matter, how hard we try it to squeeze it off, it oozes out, like it has to find a way to come out.

So now, instead of looking for a “pinko” under every rock, we look for racists under every rock. Look at your intolerance in politics and regarding those who accuse, suspect, racism, if not conscious, unconscious. So, hopefully, in the Braver Angel spirit, I can raise the question of whether there is a hyper focus on our differences that is actually counter productive to tolerance and let’s say color depolarization.

People seem to be working it out, more naturally, then force fed, it seems to me, like not even be able to remember the color of who they last associated with, just like not remembering the size of their nose.

So I just ask you, Adam and others of similar mindset, to at least reach into your subliminal biases to search whether there is not a hyper surveillance that actually counters the desired goal.

Hi Kelm, I appreciate your frequent readership! I’ve definitely heard the concern voiced that there’s been an over-reach in terms of accusations of racism, and that people on the left side of the spectrum are looking for it in every nook and cranny. I think those who voice this concern are thinking mostly about the perspective of the accusers, and not about that of the people who are impacted by this alleged racism. If we’re introduced to the experience of someone who feels unwelcome because of our inherent biases, we may be more inclined to consider the reality of that bias, as Adam did, and the power we have to do something about it.

That something doesn’t need to be condemning those of us with biases, since that would condemn the whole human race. It can simply be the act of becoming aware, and helping others to become aware.

If you’ll notice, Adam’s article and Rupa’s comments don’t include any explicit labeling of anyone as racist. But they do try to help people notice something that previously escaped their attention. I think that’s fair, don’t you?