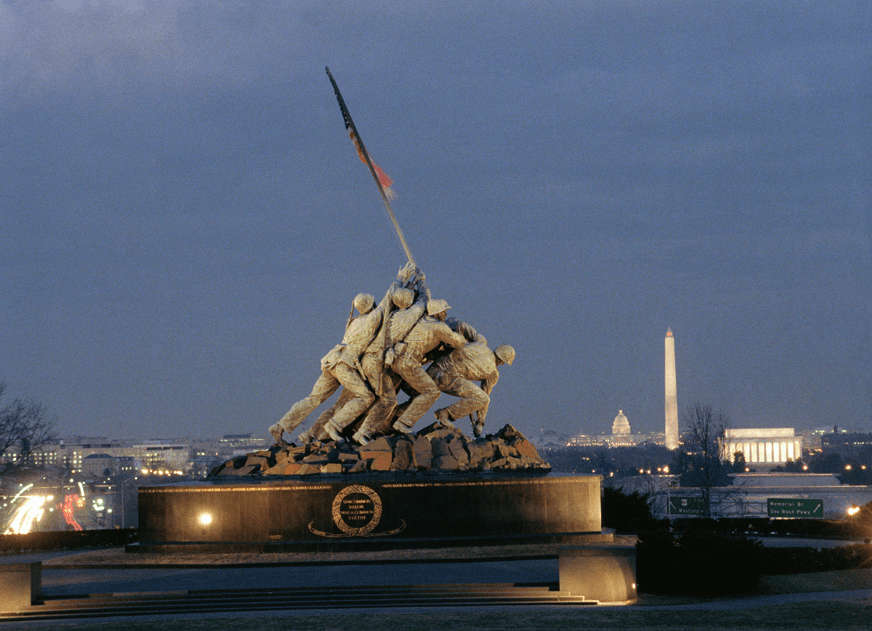

Photo: The Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia. (U.S. National Archives)

By Luke Phillips

A well-meaning, patriotic white-collar office worker is milling about, minding his own business one Memorial Day, and sees a grizzled old Second World War vet in a wheelchair, wearing a veteran cap and aviator sunglasses.

“Happy Memorial Day, sir!” greets the civilian, beaming with pride.

“Do I look dead to you?!?” retorts the veteran indignantly.

The joke, of course, plays on the civilian-military divide in contemporary American life. Memorial Day is not a holiday celebrating veterans, although there’s nothing wrong and plenty to like about being polite and deferential to old vets on Memorial Day, Veterans Day, and every other day of the year. Memorial Day, instead, is America’s holiday for remembrance of its war dead from all its wars—something of partial relevance to living veterans, of course, but not something centered around them!

This ritual—the remembrance of a country’s war dead—is both a uniquely American holiday, and one with universal connections. Essentially every society that’s lost its young men and women to war has come up with some public remembrance tradition, and a brief look at the ancient Greek military histories of Thucydides and Herodotus reminds one of the antiquity of the custom.

It is a custom fundamentally traditionalist in its outlook and mechanics—it looks to the past and encourages reflection and reverence, and to the degree that it implies any present or future relevance, it is in that the virtues of our past heroes and martyrs are the virtues we ought to emulate, in rising up to the dramas of our own day.

A physical example—the pedestal of the Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington is ringed with inscriptions of the names of battles and wars the Marines have fought for the last 250 years, from the Revolution right up to the present day. But beneath Iraq and Afghanistan, there’s an ominously empty black space—room, it seems, for seven or eight more centuries of American wars, before the Marines need to erect another war memorial. And the Marines will fight and die in those wars, as will their fellow service-members in the Navy, Army, Air Force, Coast Guard, and auxiliary departments, just as they always have, and we will honor them as we always do.

But America’s other traditions have been, paradoxically enough, more or less anti-traditions. For all the veracity of the claims of America’s Judeo-Christian natural law roots, or the enduring influence of traditional Anglo-Protestant cultural norms, or the evidence of Greco-Roman influence on various aspects of our political thought, it must be said that most Americans at most times in our history have not bothered to consider such ethereal cultural concerns. President John F. Kennedy, in his Inaugural Address, claimed Americans were “proud of their ancient heritage.” For my money, I’d say Senator John McCain’s Liberty Medal Address hits the mark a bit closer: “this big, brawling, intemperate, striving, daring, beautiful, bountiful, brave, magnificent country… the land with the storied past forgotten in the rush to an imagined future…”

Americans are, by and large, a people believing in their own reason and common sense, in the inexorable forward progress of their morality and prosperity, and in their own ability to build newer, better systems and institutions from the rotting carcasses of old ways of life. They are capable of great glories and great hypocrisies simultaneously. They are a people on the move, both across land and sea and air, and in their self-perceptions of the transformation of themselves and of all things. They are not a people inclined to intense reflection on the meaning of their society’s existence. These tendencies drive patriotic American traditionalists mad every day of the year except the patriotic holidays; and on the patriotic holidays, they are baffled by the outpourings of country-loving fervor, and confusedly grateful, but baffled nonetheless.

This is the backdrop against which, in my opinion, one ought to look at the patriotic celebrations happening today, and on Flag Day, Independence Day, Veterans Day, Presidents Day, Martin Luther King Jr. Day, and all the rest. The American people are free, and in their freedom they pursue all the mundanities that would terrify a Tocqueville and all the indulgences that would horrify a Jefferson. They should, according to “small-r” republican political theory, be as petty and ungrateful as the Israelites in the shadow of Mount Sinai, worshipping the Golden Calf as Moses brought God’s commandments down to them.

But they are not. Regardless of polarized their politics are, and however inane on balance the culture at large may be, Americans have a propensity to love their country and its storied past fanatically and un-cynically, and align their particular love for it with their own personal hopes and dreams, and their personal political understanding of the country’s heritage. Again, it shouldn’t work—but it does.

Here’s another D.C.-based example of American memorializing—the annual Washington D.C. Memorial Day Parade. Every Memorial Day, D.C. shuts down several streets along the National Mall and downtown, and a parade streams down Constitution Avenue from the White House area down to the U.S. Capitol Building.

The parade features marching bands from around the country, all traveling to D.C. on that high-school-social-studies-trip-slash-marching-band-performance that has been a staple ritual for American schoolkids of the last few generations. There are also various floats and dignitaries—many of the floats are put up by veterans’ organizations, including veterans of the Persian Gulf War of 1991, Taiwanese-American veterans, Korean-American and Vietnamese-American veterans, and of course various all-purpose VFW and American Legion groups.

But those are, for me, just the fillers. The real treat of the parade is what you might call ‘The Vision of Washington.’ Let me explain, in an unnecessarily roundabout way.

There’s a famous passage in Virgil’s Aeneid (the founding political epic poem of the Roman Empire, written two thousand years ago) commonly known as ‘The Vision of Aeneas.’ Aeneas, the divinely-sanctioned refugee of Troy and soon-to-be founder of the city that will become Rome, visits the underworld and receives a vision from his dead father, Anchises.

The vision consists, mainly, of Anchises informing Aeneas of the future of the city he is about to establish, and goes down the sweep of Roman history describing famous events and famous Roman men who will spring from the city he founds—the Latin and Punic and Grecian Wars by which Rome expanded, the internal intrigues of senators and patricians and populists, and the foundation of the Republic, the civil wars and the establishment of the Empire; such great and heroic names as Romulus, Julius Caesar, Brutus, Paulus, the Scipios, the brothers Gracchi, Augustus Caesar, Fabius Maximus, Augustus Caesar himself. It’s a fascinating exercise in reverent historical mythmaking.

I’ve always thought a good American bad-remake-version of that would be “The Vision of Washington,” where a young George Washington, holed up at Fort Necessity and impotently watching his men die in the muck around him, in the pitched frontier battle that launched the French and Indian War and ultimately set the colonies on the path of independence, received a vision of the future of the country he was about to found, America.

Perhaps the vision could be from his cultural forefathers, John Smith of Virginia and John Winthrop of Massachusetts, two prior founders of the American cultural mass then still forming along the Atlantic Seaboard. Winthrop and Smith would inform Colonel Washington of his providentially-ordained mission- to found a new nation, conceived in liberty, dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal, that would one day take its place among the nations of the Earth, and in due time transform the world.

And then, parading before the young Washington’s mind’s eye, he’d see the sweep of American military history, and the famous events and famous American men who’d spring from the nation he frees and the republic he founds, with Smith and Winthrop narrating:

“Look here, Washington—here pass the blue-coat soldiers

The Old Guard, whom you’ll command at Yorktown

And win American freedom for all time.

And when the British come again to take you

In 1812, and burn the city bearing your name, where never you’ll set foot,

These marching ragtag soldiers, under the command

Of brutal, noble, bloody, raging Andrew Jackson—they will win

And New Orleans will stay ours, and the Mississippi, and the West,

And now, in coats of Blue, see these? Grant, Meade, Sherman, Sheridan their names

Who’ll burn American fields and slay American men

In service to the Union, imperiled by sin; in service to

The honest man in black, behind them- Abraham Lincoln, greatest of his time

Whose top-hat hides a cunning mind and gracious heart.

These men in Grey behind- Lee, Jackson- betrayed their country

But were of stout, noble hearts- their descendants will go forth

To redeem the treason of their fathers in the blood of wars against tyrants.

A century anew now dawns, yet bridging the valor of the last and the technique of the new

Here prances young Theodore Roosevelt, first Roosevelt to lead this country

He and his Rough Riders, charging up San Juan, will lead America

Into a global world of dangers and opportunities. The wars of iron, horse, and wood are past;

The wars of steel, coal, oil, and air have just begun.

See stout John Pershing, commander of the Doughboy host, lead our boys

To victory across the seas, a first. See again, MacArthur with his corncob pipe

And darkened glasses; Patton, the fiery lion; Eisenhower, the steady planner from the plains.

A world kissed by freedom, they will save; the GI’s at their command will free

Peoples round the world from Axis power. When Communism rears

Its head beyond, they will fight it coldly, with the same vigor of fighting fascists with fire.

Korea—Vietnam—A thousand other lands—Iraq—Afghanistan—so many more—

See the war machines here passing, and the camouflage-bearing soldiers marching past?

They’ll all look to you, Dear Washington, for guidance, and many will not live.

They fight and die for the cause of America. And remember, First American, to be worthy;

To keep the lamp of freedom always free; to wisely wield the sword abroad for peace;

To let your better angels move you always; to bring Mankind a better way of life.

These shall be your arts, and those of your descendants. Be worthy of yourselves.”

This, in my bad and tacky pseudo-Virgilian verse, is what Smith and Winthrop would admonish Washington, in the parallel epic. And this, as well, is a reasonable description of what is, in my opinion, the best part of the National Memorial Day Parade in Washington D.C.

Between the floats and marching bands and veterans’ groups, reenactors dressed as soldiers from many of America’s great wars—the ghosts of our war dead—and their legendary commanders all stream past. The individuals I listed—George Washington, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, the Union generals Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, George Meade, and Philip Sheridan, the Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, Theodore Roosevelt, John J. Pershing, George Patton, Dwight Eisenhower, Douglas MacArthur—all march past, represented by reenactors dressed up in period garb.[i]

Moreover, small groups of soldiers march as well—the Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps, which is the U.S. Army’s main colonial/revolutionary musical group, is always near the head of the parade, and are usually accompanied by various Revolutionary War soldiers; Lee and Jackson usually have a few other Confederates on horseback with them; Grant and Meade are accompanied by black and white Union soldiers marching behind them; Theodore Roosevelt has some blue-and-tan-clad Rough Riders next to him; and the WWI and WWII generals have their own groups as well, consisting of both octogenarian veterans with their VFW and Legion hats riding in open-topped antique cars, and some younger people dressed up as GI’s to accompany. There’s even a float reenacting the famous “First Kiss” photo on V-J day in Times Square.

In the WWII floats, and those for Korean War and Vietnam War vets, the line between old history and living heritage is blurred—bringing, fittingly, the great tradition inaugurated by George Washington on down up to us. We are the pointy tip of the spear bringing that tradition forth into the future, and all the American culture and principles and liberty and heritage that our military tradition both defends and embodies into the future with it. That, in a way, is the greatest meaning of the Memorial Day parade, and of Memorial Day itself.

Military service and heritage, integral as they are to the history of the United States and to American civic culture, need not be the only way to serve your country. There are other ways to be a good patriot, with your country foremost in your heart. Memorial Day remembers those who made the ultimate sacrifice, and Veterans Day remembers those who, Cincinnatus-like, gave a portion of their time and talent and life to serving in uniform.

The example of our war dead and our veterans ought, I think, merely instill in us a reverence for the society we live in and the heritage we keep, regardless of how shallow, hollow, vitriolic, unjust, self-righteous, and bombastic it can be at times, and regardless of how often our fellow Americans fail to live up to our personal expectations and the standards we set for them. If the dead of Chattanooga, Gettysburg, Iwo Jima, and Normandy would have fought on for the cause of America—and if their surviving comrades and descendants have done the same—who are we to judge that cause unworthy, however imperfect we may be? And what better way to do honor to them, who gave the last full measure of their devotion, than remaining dedicated to the unfinished work which they so nobly advanced? Than by striving to finish the work we are in—and in our case, in binding up the nation’s wounds?

The two paraphrases above—of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and Second Inaugural Address—will be quoted quite a bit today, of course. But an earlier quote of Lincoln’s, from his 1838 Lyceum Address, might be helpful in thinking about the role of historical memory of the great moments of our past, regarding how we ought to approach the challenges of transformation and polarization we Americans face today.

“I do not mean to say, that the scenes of the Revolution are now or ever will be entirely forgotten; but that like everything else, they must fade upon the memory of the world, and grow more and more dim by the lapse of time…

They were the pillars of the temple of liberty; and now that they have crumbled away, that temple must fall, unless we, their descendants, supply their places with other pillars, hewn from the solid quarry of sober reason…”

We, a new generation of Americans, look to the storied past and see the foundations of our order; and it is our duty, as the bulwarks of that order decay and divisions arise and stagnant chaos bodes, to do our duty to our country by building anew onto that old foundation. And in a very real way, the depolarizing, synthesizing, relationship-deepening, cross-cutting bridge-building work of depolarizers around America, is our meager yet inspired attempt to do justice to the heritage which came before us, and the future that will come.

For much of my early life, I wanted desperately to serve the United States of America in uniform. My father was a naval officer, as my brother now is; and growing up in that world, I saw military service as the prime path to patriotic devotion, and tailored my studies towards it. I ultimately wound up unable to commission into the U.S. Navy due to health reasons, and my subsequent attempts to enlist in the National Guard, apply to the Central Intelligence Agency, and become a Foreign Service Officer for the State Department all failed. For a time I felt a great dismay, knowing I’d never join the pantheon of patriot-heroes that is the tradition of American public service in uniform and in the security, diplomatic, and intelligence services.

But in the time since, it has become ever so clear to me that one can serve their country out of uniform as well. In particular, the world of policy research, political commentary, and civil public conversation more generally—which I’ve since entered and which is an intellectually stimulating and personally fulfilling place to be—is a place where one can honor the war dead of the past through working for a more enlightened discourse. It’s different work, of course, but done well there’s a lot of good to be done there.

So, my fellow Americans, with the spirits of our great heritage and our bright future in mind, let us move forth and depolarize America. Let us aim to serve, and go from there. Happy Memorial Day.

[i] The guy who portrays Andrew Jackson every year, whoever he is, is always brandishing his sword and yelling things at the crowds, which I’ve got to say seems like one of the most fun volunteer gigs any human being on this planet has the pleasure of doing.