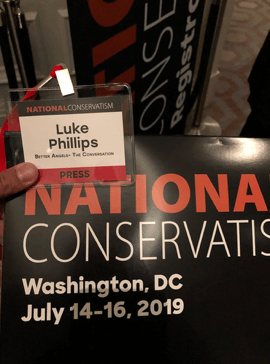

While I was covering the National Conservatism conference in Washington D.C., a high-profile gathering of detached conservative intellectuals discussing lofty visions of the world, the American news cycle was parading around two very concrete controversies with relevance to the conference’s themes. Nike’s withdrawal of a new product designed around the old Betsy Ross Flag—ostensibly responding to NFL star Colin Kaepernick’s concern that the Betsy Ross Flag bears connotations of slavery—sparked a vast public controversy over the nature of American patriotism a few weeks ago. Even more saliently, President Donald Trump tweeted a message that can be reasonably interpreted as racially ignorant at best, and perniciously racist at worst, implying that four very progressive Congresswomen are not truly ‘American’ because of the color of their skin. The House of Representatives passed a resolution condemning Trump’s statement.

Neither of these controversies was mentioned in any detail, so far as I can recall, in any of the public sessions I attended at the National Conservatism conference, not even the ones assessing the nature of American identity. That was a tremendous missed opportunity, but perhaps to be expected of a gathering apparently intended to develop a new ideological consensus for the coming decades. At the very least, the fact that those two stories swirled around outside the Ritz-Carlton made clear the significance of the work being done there.

The National Conservatism conference essentially tried, and partly succeeded, to restore greater public legitimacy to the tradition of thinking on American identity that privileges the customs and traditions of the American heritage, the grandeur of the American historical experience, and the virtues of past Americans, rather than merely the aspirational reformist tradition and the abstract ideals of the Declaration of Independence and Bill of Rights. I’m of the opinion that the dangers some saw in the conference’s mission were overblown—a writhing pit of Alt-Right vipers, this was not. On the other hand, the revolutionary world-historical significance some at the conference seem to have attached to their work seems equally overblown. Like most American things, excessive hay was made about something essentially good but rather small, whose dark side mostly manifests itself in ridiculousness rather than malice.

Michael Lind wrote in 2014 that American politics further into the 21st Century would increasingly look like an ongoing contest between “Liberaltarians” in the coastal metropoles, and “Populiberals” in the interior suburban expanses. Liberaltarians, he argued, would be social cosmopolitans favoring free-market mechanisms; Populiberals, he suggested, would be social localists favoring statist policy measures. To the degree that Lind’s split is happening within the conservative movement, one could think of Bush-era Neoconservative intellectuals like Bill Kristol as Liberaltarians, and Obama-era Reformicon intellectuals like Ross Douthat as Populiberals. The Liberaltarians have found their institutional home at the Niskanen Center; the Populiberals have had some voices, but no true institutional home yet, and it seems that the new Edmund Burke Foundation, which put on this conference, is attempting to fill that niche.

The Edmund Burke Foundation calls itself “a new public affairs institute dedicated to developing a revitalized conservatism for the age of nationalism already upon us.” It looks like it’ll be setting up think-tank operations in D.C. in the coming months. Many of its leaders are major names in the world of traditionalist conservative journals—American Affairs, The Claremont Review of Books, Modern Age, more. Their targets on the left are “globalism” and “identity politics.” More interesting are their targets on the right: free-market libertarians, democracy-promoting neoconservative hawks. They oppose the atomizing tendencies of libertarian economics, and the messianic qualities of neoconservative interventionism, for the same reasons they oppose messianic globalism and divisive identitarianism. These are communalist social conservatives, more than anything else; there is a broad divergence between their definitions of nationalism, but a general agreement on the necessity of rootedness and community unites them all.

The four keynote speakers—Peter Thiel, Tucker Carlson, Ambassador John Bolton, and Senator Josh Hawley—were an interesting crowd, and probably hint at the ways a future National Conservative movement would manifest itself in public life outside the cloistered intellectuals at the policy journals. That said, more of interest was said on the panels, than in the keynote addresses.

And just as the keynote speakers themselves were a politically diverse group, so were the non-keynote participant speakers. It seems to me that there were four main factions represented among the speakers:

Catholic Traditionalists, like Patrick Deneen, First Things editor Rusty Reno, Mary Eberstadt, and Luma Simms; devoutly religious thinkers whose primary concerns were on social connection and social policy, who express a deep skepticism towards a particular vision of “liberalism” including internationalist capitalism, and are the most theoretically communitarian of all the groups represented;

Socially Conservative Libertarians, like Amity Shlaes and Richard Reinsch, whose philosophies don’t deviate much from originalist constitutionalism and small-government libertarian economics, but whose understanding of natural law and moral order makes them primarily socially conservative;

Fusionist Conservatives, like Yuval Levin, Michael Barone, Christopher DeMuth, and Rich Lowry, people in the National Review network who generally (and probably rightly) see this new nationalism as being more or less a slight course-correction from “muscular internationalism, social conservatism, and supply-side economics” toward the more rooted “American nationalism, religious communitarianism, and market economics,” and thus a mere adaptive evolution of the old conservative consensus;

and West Coast Straussians, like Christopher Buskirk, Michael Anton, Charles Kesler, and Arthur Milikh, who were the most strongly Pro-Trump participants and certainly some of the most ideologically eloquent, who don’t demand a reversion to pre-liberal norms the way the Traditionalists do, but do demand the expungement of the progressive varieties of liberalism from the American creed.

Additionally, beyond these main factions and main speakers, there were individuals present whose ideas further highlight some of the assembled conference’s internal tensions.

Julius Krein, editor of American Affairs, is the archetypal economic nationalist wonk for our age, and was one of few speakers to talk about concrete policy ideas beyond immigration restriction. Oren Cass, a former Romney advisor and currently a leading GOP policy wonk, spoke a bit about industrial policy one of the evenings. (It is unfortunate that he did not also speak about labor policy.) Yoram Hazony, author of a recent book on nationalism, was probably the single most non-liberal or anti-liberal speaker there (and one of the more self-contradictory ones,) but deserves credit for making the first popular moral case for nationalism post-Trump. Daniel McCarthy, editor of Modern Age (the magazine established by none other than the arch-traditionalist Russell Kirk,) made some interesting differentiations between democratic-republican liberalism and pragmatic liberalism in the history of political thought, a seemingly-arcane subject with immense implications for how we understand the American Founding.

Unsurprisingly enough, the event was largely and proudly Pro-Trump in its practical politics. David Brog, one of the hosts, went from golden quips like “we don’t want to be left alone—we want to be connected, connected to each other, connected to our ancestors, connected to our descendants. Because these connections give us meaning,” and soaring invocations of the great Anglo-American national conservative tradition of Edmund Burke, Benjamin Disraeli, Alexander Hamilton, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt, straight to proud endorsements of Donald Trump’s apparently virtuous, unproblematic, entirely-populist ascendancy to the Presidency of the United States.

Michael Anton, a.k.a. “Publius Decius Mus” and author of a notorious (and in my opinion, needlessly tasteless) essay comparing the choice between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton to the choice whether or not to storm the cockpit of Flight 93 on September 11th, 2001, made an appearance likening some of Trump’s apparent convictions to classical virtues of anti-imperial liberation. On occasion, some of the National Review-affiliated speakers raised concerns about Trump’s divisiveness and ethereality, but for the most part, Trump was praised as being a figure returning America to a nationalistic sobriety after the daze of the post-Cold War world.

In their defense, it is assuredly more productive to assume that Trump was representative of various trends, benign or malign, with which pragmatic political operators and honest political thinkers must grapple with and harness in the years or decades to come if they want to remain relevant. But the conference’s functional elevation of Trump to secular sainthood status is an almost comical contrast to the daily realities we see on the news cycle. The only thing more ridiculous than the left’s ‘Trump as Orange Hitler,’ you might say, is this new right’s ‘Trump as Orange Churchill.’

Despite these foibles, I reiterate- the National Conservatism conference was not, by any means, a proving-ground for white nationalist ideas, a legitimator of alt-right sentiments and conspiracies, or a cradle of violently neo-reactionary political projects. I am sure there were some alt-right personalities present—I did see the notorious blogger Curtis Yarvin, a.k.a. “Mencius Moldbug,” present as an attendee, looking disappointed—but they were not the centerpiece. Far from it.

In fact, in his opening remarks, Mr. Brog elaborated that the conference received admission requests from various explicitly white supremacist and white nationalist thinkers, and rejected every one. To further highlight the point, he said to the assembled body that if any white supremacists whose conception of American national identity was based on race were present in the audience, they were free to leave. “We are nationalists—not white nationalists.” (At this point, it would’ve been helpful had Brog addressed and rejected President Trump’s tweet against the Democratic Congresswomen; alas, he did not.)

In a way, communitarian nationalist conservatism is in the second or third most challenging piece of intellectual ground to occupy and argue for in the age of globalization, in no small part because of the lingering legacies of racialism and the resurgence of racialist resentment and violence on the fringes of Western societies. It is unfortunate that the onus falls on the Edmund Burke Foundation and its conference speakers to prove that they are not racist; but for the most part, I am of the opinion that they amply did, both with Brog’s remarks and in the programming across the conference. Again—a writhing pit of Alt-Right vipers, this was not.

I was surprised to hear multiple times, scattered throughout the conference, references to things we at Braver Angels have been working on quite a bit. “What can bind up our wounds? A new patriotism…” “We need to love our fellow citizens… We need to internalize the reality that the futures of every American citizen are inexorably combined…” Brog even quoted our favorite passage, from Abraham Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address, regarding how fellow American citizens must treat each other: “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies… The mystic chords of memory… will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the braver angels of our nature…”

All this talk about love of country, love of countrymen, and love for American heritage is good. It is good in reality, and it is good in principle. Unfortunately it stood, in the conference, in stark contrast to the seething contempt many speakers expressed towards the cosmopolitan American left, both of the globalist and identitarian varieties, and to the kind of amused contempt they expressed for conservative libertarians. Yes, a half-depolarization is better than polarization, and it is better to give lip service to the value of civic friendship than not to; but it helps no one when supposed goodwill is ideologically blind to the existence of opposing intellects as worthy objects for civic love. Some speakers, including Peter Thiel, even suggested that there is no room on the left, at the moment, for useful conversations on American nationhood and identity. This attitude is directly antithetical to a nationhood of civic friendship, charity, and love, no matter how much it claims to be the necessary foundation of those things.

There’s a productive tension between the principles, ideas, and ideals of the American creed, and the customs, traditions, and experiences of the American heritage. Broadly, blue liberals are patriots who love America’s principles, ideas, and ideals; while red conservatives, and these nationalist conservatives, are patriots who love America’s customs, traditions, and experiences. These rival conceptions need not be exclusive against each other, but they easily can be, especially when spun into messaging for political coalitions. This is usually a winning strategy—it seems there is nothing Americans hate more than their fellow Americans holding different definitions of America.

The national conservatives are as human as any of us, in holding their particular rooted vision of American identity as the true, absolute, legitimate one, and the ideational one to be at worst a malign, perverted heresy and at best a cute little obstruction. A little dose of the Isaiah Berlin/Reinhold Niebuhr notion that American history and identity can’t, and shouldn’t, be boiled down to a single reality, and can’t make pure moral sense, would seem to be in order.

The best that this group can probably do is restore, to a heavily imbalanced national conversation on American identity, the legitimacy and dignity of heritage-based nationhood and communitarian conservatism as a driving, honored force in the discourse on American politics and culture. It can and must supplement, but cannot and must not replace, the ideas-focused neoliberal and libertarian understandings, and the reformist-focused progressive and evangelical understandings, of how American history and identity are manifested. It cannot conquer and dominate them, and must not attempt to. America is neither idea nor nation, but both and more, an ongoing conversation between principles and experiences that over time forms the ongoing legacy and spirit of America.

A serious pro-communitarian politics which, accepting the liberal nature of American order, nonetheless can soberly reform it for the common good, and work to oppose and defeat racialism in all its ugly forms, while promoting a politics of national unity in our changing, dangerous era—this is what the national conservative movement can become, if it is prudently managed and well-led. It is also the kind of movement that depolarizers will need to work with in the future, as it brings a native temperament of communalism and warm civic pride to a depolarization conversation dominated, at the moment, by liberals and libertarian conservatives. Among the ways to be American, the national conservatives have one particular way that must be present in any conversation and project on the future of American unity.

But ideas and speeches and manifestos are one thing—the world of vote-counting, media-saturated, democratic American politics is another thing entirely. Whether or not national conservatism can graduate from Trumpish populism and esoteric philosophizing, and into a more stable and sophisticated political project, will be an important story moving forward.