Each year, as the Jewish holiday of Passover approaches, I get to thinking about what strikes me as a central message of the biblical story of Exodus recounted at the Seder meal—the essential sadness of all human suffering, whether by those we love or those we’ve come to see as “enemies.” A few years ago, I reflected on this idea that we are all God’s children, an idea I can embrace despite not coming from a place of spiritual faith. I would characterize my faith as more focused on humanity, the core belief that there is good in all of us, even as much of it has yet to be uncovered.

This year, especially, seems to be a time when that lesson needs to be reinforced. As the Russian military bears down on Ukraine at the behest of a seemingly isolated, paranoid and vengeful Vladimir Putin, everyone that I know is pulling for its vanquishing defeat. I’ve certainly taken solace in the news about the struggling and demoralized Russian troops, and have supported the full weight of international sanctions being imposed on the Russian economy in the hopes that its people—not least of all its oligarchs—would exert the pressure needed to bring this war to an end.

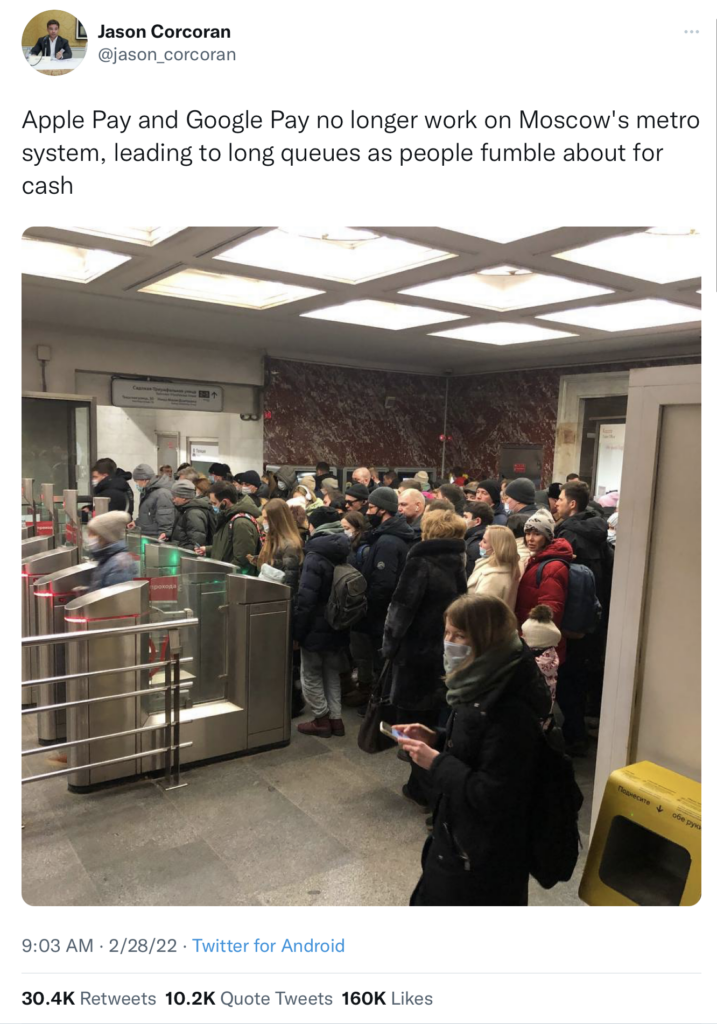

I’ll even admit to a surge of schadenfreude at seeing posts about the long lines of Muscovites trying to access the metro after electronic payment systems stopped working.

But the glee with which I have witnessed Americans reacting to this sort of news snapped me back to the realization of how easy it can be to lose sight of the cruel reality so many Russians face. Many of its most globally interconnected citizens, especially those in its IT workforce, have been streaming out of the country en masse since the start of the invasion, as they’ve realized the limits to their future in a country increasingly isolating itself from the rest of the world.

Even as they do so, there are those who refuse to welcome them. In this BBC report, tech workers in exile recounted their struggles with finding housing, as Airbnb hosts put these emigrants’ Russian or Belarusian nationality ahead of their humanity when considering whether to provide for basic needs like shelter.

“‘They think we are running away from Russia because Apple Pay no longer works there,’ Igor complained. ‘We are not running for comfort, we’ve lost everything there, we are basically refugees. Putin’s geopolitics has destroyed our lives.’”

This xenophobia paints an entire people as tainted by the sins of the few, and it begets an endless cycle of hurt that bounces from one group to another.

Many of us who see the polls within Russia citing overwhelming support for Putin and the war try to focus on the most charitable explanations—that the lack of accessibility of information outside of state-controlled media blinds them to reality, and that the polls may be seriously inflated by self-censorship among Russians. Still, as is usually the case, the picture is more complex.

Washington University professor James V. Wertsch argues in the South China Morning Post that a vast swath of Russian society has truly bought into “an ‘expulsion of alien enemies’ narrative” that colors their view of their geopolitical experience. This thread, Wertsch points out, includes the celebrated Nobel prize-winning Soviet dissident author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, whose pan-Slavic nationalism fostered an ever more strident opposition to Ukrainian independence towards the end of his life.

A distrust of outsiders and their influence is far from uniquely Russian, of course. In fact, as I mentioned in my earlier piece, it lies at the heart of the story of Exodus, with the Pharoah of Egypt demonizing the Israelites as a potential foreign threat, and pushing his people to subjugate them with slavery.

It was precisely the Egyptians’ loss of their ability to empathize with the Israelites that makes the lesson of our sadness over Egyptian suffering so important. If their humanity were to remain easily accessible, it would make our reciprocal demonization much harder. But because their actions appear so monstrous, we must be reminded through the power of biblical narrative to return to the basic truth of our shared human story.

There is no shortage of examples of societies retreating into themselves in the face of great fear and anger towards outside forces. As someone focused on the challenges of U.S. political polarization over the past several years, I see this fear of outsiders as a key component of the internal demonization we’ve experienced.

Prior to the modern age of global interconnection, the tribalism that fostered this fear made sense. Our early human ancestors’ healthy distrust of outsiders kept them safe from ambush and perpetuated their genetic legacy. But with the rise of mass remote communication, we have the tools to encounter one another intellectually even before we meet physically, letting us connect as humans before we clash as adversaries.

To truly connect, though, we must be willing to face one another’s fears, and acknowledge just how human those truly are. We must go beyond the anger and vengeance of those who see us as the sinners, and focus on the narratives that create it.

Yes, we should support our Ukrainian sisters and brothers who are the victims of this destructive narrative with all we can muster. But unless we keep in mind the essential—and attendantly flawed—humanity that we share with the Russian people, and strive to connect with them in any and every way possible, we cannot hope to transcend the cycle of aggression that continues to haunt the human race.